What is a Cenote?

What is a Cenote and how many are there?

Cenotes are objects of stunning natural beauty, found in many places around the world. But what is a Cenote? Find out more below.

The best place to see them is in the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico. They are great places to visit.

My family and I love to swim and snorkel in the cenotes. You can even scuba dive in cenotes!

But what is a cenote? What types of cenotes can you explore on holiday? Why are there so many cenotes in the Yucatan? How were cenotes formed? Let’s look at each of these questions.

Along with Mayan ruins, it’s no wonder cenotes are among the most popular tourist destinations in the Yucatan. Some cenotes have become tourist advertising icons, like Cenote Ik Kil, the iconic Chichen Itza cenote.

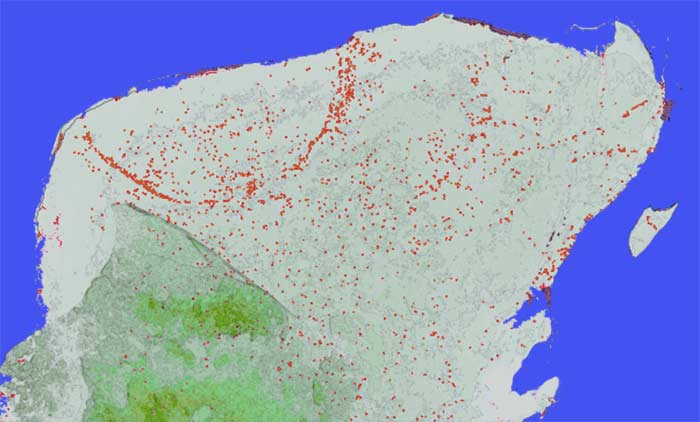

There are between 6,000 and 10,000 cenotes in the Yucatan Peninsula. Less than a third are exploited. This is open to question as no one knows how many cenotes there are in the Yucatan. The reason for the lack of clarity is the terrain of the Yucatan. With much of Yucatan still covered in jungle, areas that have not been inhabited for centuries have yet to be re-explored.

Lidar (an airborne laser scanning tool used by archaeologists) is now being used to uncover lost Mayan cities. In July 2023, the BBC reported the discovery of the Mayan city of Ocomtún in the state of Campeche. This city is thought to have covered more than 50 hectares!

If a city this size has just been discovered, how many cenotes are in the Yucatan Peninsula waiting to be uncovered? One Yucatan newspaper reported in May 2023 that hundreds of cenotes had been discovered during the removal of forests for the Mayan train.

Table of Contents

Why are there so many Cenotes in the Yucatan?

Cenotes are natural sinkholes found across the Yucatan Peninsula. The peninsula is basically a large limestone plateau and this is the reason there are so many cenotes here.

The basic story about the origin of cenotes is that limestone is porous and, over long periods, water percolating through the rock leached away some of the limestone. In some parts of the world, this leaching has created amazing and bizarre above-ground rock formations. In the Yucatan, it created a series of cave systems, from small to incredibly long.

Cenotes form when the roof of a limestone cave collapses. This may completely expose the previously hidden water to the sky. Or it may create submerged pools of water, with limited or no view of the sky.

In addition to the basic cause, two additional factors may have affected the creation of cenotes (there are other theories). In the east, along parts of the Caribbean coast, seawater entered the outlets of the underground freshwater basin (aquifer). That formed a more corrosive solution increasing the leaching of limestone, leading to more caves and collapses.

In the north, the massive impact of the Chicxulub asteroid led to the formation of a ring of cenotes in Yucatan.

How are Cenotes linked to the Extinction of the Dinosaurs?

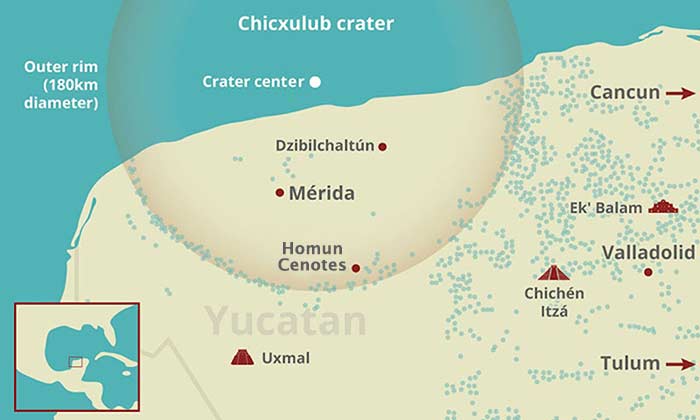

According to scientists, some 65 million years ago a large asteroid crashed into the earth near what is now Chicxulub near the town of Progreso in the State of Yucatan. The asteroid measured six miles (10 kilometers) in diameter. When it crashed into the earth, it created the Chicxulub crater. That impact is most famous for being responsible for the extinction of dinosaurs.

Less well-known is its other consequence. It is thought that the asteroid created a large number of cenotes as a result of the impact. The resulting crater is reckoned to be about 110 miles (180 kilometers) in diameter and 12 miles (20 kilometers) deep.

It is now covered by the limestone plateau. Half of that hidden crater lies out in the Gulf of Mexico. The other half is inland. The semi-circular edge of that crater runs from, roughly, the coastal towns of Celstun to the west to Dzilam de Bravo to the east of Progreso.

Scientists have pointed out that the inland edge of the crater, which lies about 55 miles (90 km) inland, matches a series of cenotes in what is known as the Ring of Cenotes. This is 4 miles (5km) wide ring with many well-known cenotes.

It is thought that the differences in rocks along the edge of the crater led to changes in the aquifer there. These changes enabled or affected the rate of limestone leaching. This ultimately led to the creation and collapse of underground caves creating the large number of cenotes that lie on the ring.

Click to see: 10 Best Day Trips from Merida including Progreso

What are the Types of Cenotes in the Yucatan?

The cenotes in Yucatan typically fall into one of three categories:

Open cenotes – no climbing down stairs and clear sky above

Open cenotes are caves where the roof has completely collapsed, leaving the base exposed to the sky. The water is easily accessible at ground level. Examples of this type are Cenote Carwash, Cenote Azul, or our favorite Cenote Yax Kin.

Semi-open cenotes – stairs down and a hole in the roof

As their names suggest, they are mainly underground but due to a partial roof collapse, they are accessible to the elements. Most can be accessed by steps through the roof opening but a few, such as Cenote Xooch, have an entrance through a tunnel in the side wall of the cavern.

Examples of other semi-open cenotes are Cenote Kankirixche and Cenote Yaxbakaltun.

Underground cenotes – no sky!

Underground cenotes are normally part of a cave system, with no natural light. We haven’t visited this type of cenote as they are normally more difficult to visit due to their structure and depth (and one of our family has an aversion to enclosed spaces!)

Those near Coba (Multum-Ha, Tamchach-Ha, and Choo-Ha) are among the easiest to explore. They are close to each other, making it easy to visit all three on the same day. They are also popular.

Who or what uses the Cenotes to survive?

Due to the lack of rivers and streams, cenotes were an important source of water for Mayans in the Yucatan. In many places they still are.

The word ‘cenote’ is a corruption of the Mayan word “tsʼonoʼot” (also shown as “dzonot” or “ts’onot”) which means ‘well’ as in a water well. Their life-giving properties led to a strong spiritual significance.

Aside from humans, cenotes offer water relief to a lot of wildlife. Marine fish and freshwater fish, shrimps, eels, turtles, and other creatures live within the cenote waters. Amphibians rely heavily on the cenotes for breeding.

Crocodiles and manatees use cenotes as well. In the deeper, darker cenotes the animal life has adapted to the lack of life through loss of pigmentation and in rare cases, loss of their eyes. Normal cave-dwelling insects and arachnids can be common in the caves.

Can you Scuba Dive in a Cenote in the Yucatan?

You can snorkel in most cenotes, but you can’t use flippers in some cenotes.

Cenote scuba diving is an additional option in several cenotes. If you’re qualified, this is a unique opportunity to explore hidden, underwater worlds. The scope of scuba diving varies from one cenote to the next.

Some cenotes offer a basic dive in a deep pool, with the opportunity to see fish and rock formations. Others have caverns to explore and a few have underwater rivers or tunnels you can enter. (You need to have cave diving certification to dive in most caves and tunnels).

The variety of wildlife you can see ranges from freshwater fish to saltwater fish, turtles, and even crocodiles if you’re lucky.

Scuba diving in Casa Cenote – also known as Cenote Manati (or Cenote Manatee) – involves access to the underground tunnel between the sea and the cenote. Cenote scuba diving tours are available from Cancun, Playa del Carmen, or Tulum. They will organize everything for you.

How to Be safe while scuba diving in Cenotes

Safety is paramount as, in many cases, cenote scuba diving is in more remote locations or away from a main road. Sadly, each year there are reports of divers who have died in a cenote. Some have been qualified, experienced divers, not uncertified tourists out for a thrill.

Many scuba diving cenotes have a good reputation but always check the quality of the cenote offering the diving. On arrival inspect their kit if you haven’t got your own.

Some cenotes have specific rules about the dives and how you conduct yourself – make sure you understand and follow them. They are for your benefit as much as the cenote.

The water in a cenote is normally crystal clear but near the bottom silt can be kicked up, which quickly destroys the visibility. Without currents, the silt floats for some time. Even with crystal clear water, the depths and angle of the sun can make parts of the dive very dark.

Not all cenotes ask for the correct certification. If yours doesn’t be cautious. You don’t want to be down deep and confronted with inexperienced divers, especially in the dark.

Always dive within your limits and be extra careful when scuba diving in cenotes with others who are not.

How did Cenotes affect Mayan Religion and Customs?

Like many of the other civilizations in the region, the Mayans believed in a range of powerful gods and deities that lived in a supernatural realm. To the Mayans, it was necessary to keep these gods happy through regular sacrifices.

For many Mayans, certain cenotes were the gateway to the underworld, Xibalba. To them, Chaac, the god of rain lived at the bottom of some cenotes. This gave those special cenotes a sacred significance.

So, in addition to providing water, cenotes were also used as a location for sacrifice. In many cases, the sacrifice would be gold or other artifacts. There are reliable testimonies of human sacrifices being done at several cenotes when asking for favors from the gods. Normally, this was for good harvests.

Even today, some Mayans hold that cenotes are sacred, holding to many of their ancestors’ beliefs, although the number is falling. They hold that some cenotes grant wishes or have magical curative powers. Others will visit or make a pilgrimage to a special cenote to ask for guidance or to make an offering for a favor.

Even for those Mayans who don’t hold to the full spectrum of the old Mayan belief system, many feel that cenotes are sacred and should be treated with respect.

And we, as visitors, should treat them with that respect.

Cenotes in the Yucatan – keep them and yourself safe

Are cenotes safe to swim in? Yes, if you take the sensible precautions shown below. But cenotes are not necessarily safe from us! While they offer experiences you are unlikely to get at home, they are fragile. Here are some simple rules for your safety and that of the cenote:

Use bio-friendly sunscreen

The water in a cenote is not affected by tides or rivers. In most cases, what’s in the cenote leaches up through the limestone. If you use a standard sunscreen it will remain in the water long after you have gone. The fish and plants in cenotes rely on the purity of the water. Oils and lotion will adversely affect that purity.

Most cenotes now have signs asking you to only use bio-friendly sunscreen.

Shower before you enter the water.

For the same reason, most cenotes insist you shower before entering the water. Body oils, creams, etc., will all end up in the cenote water.

Wear reef shoes

Many cenotes have rocky bottoms or even rocky outcrops you have to negotiate to get into the water. Some are rough and allow for a good grip. Others, due to the water and sunlight, are covered in algae – these can be very slippery as I’ve found to my cost a few times!

Semi-underground cenotes invariably have wooden stairs down to the water. These can also be slippery.

Wear a hat

Open cenotes are great but it’s easy to forget just how hot the sun is. Even with sunscreen, it’s a good idea to have a hat handy.

Is Snorkeling good in Cenotes?

Cenotes snorkeling offers great opportunities to see things you can’t if you’re just swimming at the surface. Fish, stalactites, turtles – there’s much to see underwater. Most cenotes allow snorkeling and you can often rent snorkels and masks at the cenote. But I’ve never liked the thought of putting an old, much-used snorkel in my mouth. They don’t take up much room in your suitcase, so consider bringing your own.

Take your Rubbish with you

In July 2023, a report in the Yucatan Times said over 4 tons of garbage was removed from cenotes in Yucatan state in 2022.

Reports from cenotes in Quintana Roo paint a similar sad picture. This is a reminder that we all have a responsibility to bring any litter home with us when we visit these beautiful and hidden gems.

The Mayan Train and Cenotes – A problem?

The Mayan Train or Tren Maya project is proving to be very controversial.

At first glance, it looks like a great idea. It will run about 950 miles (1,470 km) around the Yucatan Peninsula. The aim is for it to provide access to many famous landmarks for tourists and jobs for the local inhabitants. These jobs might be important to those living in some financially impoverished parts of the Yucatan.

Parts of the project have been completed and tourists and locals are riding the train.

How does the Mayan Train affect Cenotes?

The Yucatan Peninsula contains between 6,000 and 10,000 cenotes. As mentioned above, less than a third have been explored.

By their very nature cenotes are fragile. Not all are exposed to the sky (see the types of cenotes below). Some are underground caverns with rivers running through them. Scientists confirm that some cenotes have roofs that are only 10 inches to 2 feet (20 to 60 cm) thick. A friend of ours can push sticks into some parts of her garden to reveal small underground caves!

In some places, the limestone base of the Yucatan plate is thick enough not to cause concern. But in other places, this is not the case.

Section 5 of the Tren Maya, between Playa del Carmen and Tulum, is one such problem route. The route has been changed several times due to complaints from hotels and problems with roads. Part of the new route runs across areas known for their large numbers of cenotes.

By law, projects like the Tren Maya require environmental impact studies. The government says their study showed the impact on cenotes would be insignificant. Environmentalists claim none was ever done.

Trust was further lost when the government exempted all parts of the project from any need for permitting. They claim it is a national security project. As such it should avoid normal permits and reporting issues.

What is really happening to the Cenotes?

I am being careful to avoid partiality. You will have to decide for yourself what the risk to the cenotes really is.

The biggest problem is a perceived lack of transparency. There is a serious lack of trust between the government and the environmentalists. It’s become a political issue. Both sides pose strong arguments (how valid they are is your decision).

This project is being rushed to get completion before the end of the current government’s term in office. The rush is blamed for several shortcuts.

On the one hand, the government has said on many occasions that they have surveyed and checked the location of all the cenotes involved. They are determined, they say, to protect these important parts of the Yucatan heritage. After all, they say, it is the source of drinking water for over five million Yucatecans.

On the other hand, environmentalists have published photos of 3-feet-wide pillars driven through the roofs of cenotes. They have shown images of damage to other cenotes.

The bottom line is that the Mayan Train will thunder across many cenotes. Pillars now penetrate the roofs of some caverns. Limestone is a fragile material that doesn’t deal well with vibration.

The Tren Maya, if the environmentalists are right, is the biggest threat to cenotes since the Chicxulub asteroid. Or, according to the government, it could be a huge boon to the local economy and the start of a new age of tourism across the Yucatan Peninsula.

The Mayan Train is now a fact of life. Time will tell who is right.

David Haggett

Copyright 2026 www.wonkycompass.com